Why did you leave your hometown of Pyongyang?

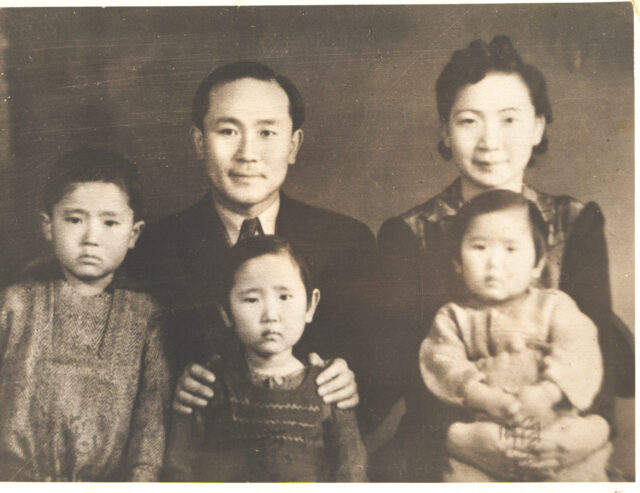

I left Pyongyang in 1947. Pyongyang was under Russian military authority at the time. Life for my family had not been easy and was about to get worse. During the Japanese occupation, my good-natured mother, Song Kyung-Shyn, surrendered her brass housewares and even her wedding ring to the Japanese army, who supposedly needed more metal for arms. When the Russians and Chinese militaries arrived, my parents’ music school was shut down, and the rest of the family properties had to be handed over to the armies. My rebellious father refused to join the communist army. When we learned that soldiers were coming to arrest him, my parents decided that it was time to escape to the south.

What do you remember about leaving?

I was awakened in the middle of the night and told that we were going on a long journey. I could not take any of my toys, and I would have to be very quiet. I had no idea that my family planned to escape from Communist rule. Between us and Seoul, there was a desolate, heavily armed frontier. In that no-man’s land, Russians were known to shoot anything that moved. Nevertheless, there were secret networks of paid workers who helped refugees to cross the 38th parallel. My parents planned to use that clandestine network to get the family to safety in Seoul. We were left with my grandmother in a remote settlement outside Pyongyang. I did not know where my parents had gone for three months.

As a child, I hardly understood the meaning of the 38th parallel, but it seemed so important to my parents. I thought that it traversed the entire world and that everyone lived on one side or the other. I wondered, ‘Why the number 38? Were there 38 soldiers guarding it? Was it made of 38 walls? And how did I ever get from one side to the other?’ I understood crossing a river or a room but not a national border.

Many refugees from North Korea left empty-handed. How did your family survive?

My father, Yoon Doo-Sun, had a good sense for business. Back then, milled wood was like currency and more valuable than gold in the south, where there was an acute housing shortage. My father left on a motorboat with his lumber and traveled south by night along the coast. When he arrived in Seoul, he presented a letter of introduction to a friend who worked with the border authorities, thinking that it would serve as legitimate identification. Instead of giving him refuge, his friend confiscated his lumber, accused him of being a spy, and threw him into Seoul’s Namsan Prison.

What about your mother?

My mother stayed behind because she was about to give birth. She learned of my father’s imprisonment through a network of women traders who crossed the 38th parallel to sell gold. After giving birth to a stillborn baby, she was determined to go to Seoul alone to free my father. Her cousin, Park Keung-Shi, was an influential businessman in Seoul and would be able to help.

I can hardly imagine the courage it took for her to leave home. Because she was too weak to walk, she hired a rowboat owned by a family who lived near the border. They hid her under the boat’s planks, where she lay all night. Just before dawn, she walked onto the shore south of the border. She carried one small bag of possessions from her past life into the new.

How did you travel?

My mother’s loyal sister, Song Do-Shyn, traveled back across the 38th parallel from South Korea to fetch me and my siblings. For the first part of the journey, my family was able to hire a truck. Then the older children had to walk, and my aunt carried me on her back. My four-year-old sister, Kyung-Cha, and older brothers, Duke and Duk-Yong, walked for almost two days and nights. When we got to the 38th parallel, men were hired to carry the children across the border. This part of the journey had to be completed in the dark. Russian soldiers spotted us on our first try and chased us back to the north. We set out again by a different route. When we finally made it to Seoul, we had lost a lot of weight.

During our travels, I became very ill and ran a high fever. Uncertain that I would ever see my parents again, I would wake up from nightmares. The recurrent dream that I had for many years was about refugees crossing an icy river at night. The currents were strong, and chunks of broken ice bobbed in the black waters. The bridges had been blown up, so everyone had to cross by foot. In my dreams, I saw a woman who drowned when pulled down through the ice by the weight of the baby on her back. I doubt that I ever saw such events in real life. The dreams were much more frightening because I became the baby in the dream.

How do you think this childhood experience influenced you?

Growing up, I always felt that global events can affect your daily life. Wars, climate change, terrorism, and financial crises can turn your world upside down and take away everything you love. I have also always assumed that politics could go in the wrong direction at any time. The sense of insecurity can have positive effects because it inspires you to act instead of assuming someone else will work it out for you. It also prepares you to accept sudden disasters, act quickly, and overcome fears.

End of Section