When Charlotte Bunch talks about feminist politics, we all listen. She isn’t a shouter; on the contrary, she speaks in a steady, careful tone, as if she is measuring the impact of each word. She particularly cares about how her opinions affect others.

According to Gloria Steinem, Bunch is a touchstone of the women’s movement. Steinem often said, “Sooner or later—and on any hard questions of feminist theories of tactics comes—one is likely to hear: ‘But what does Charlotte think?’” Inducted into the American National Women’s Hall of Fame, Bunch is best known for her leadership in putting the concept of “women’s rights as human rights” onto the agenda of the 1993 Human Rights conference in Vienna.

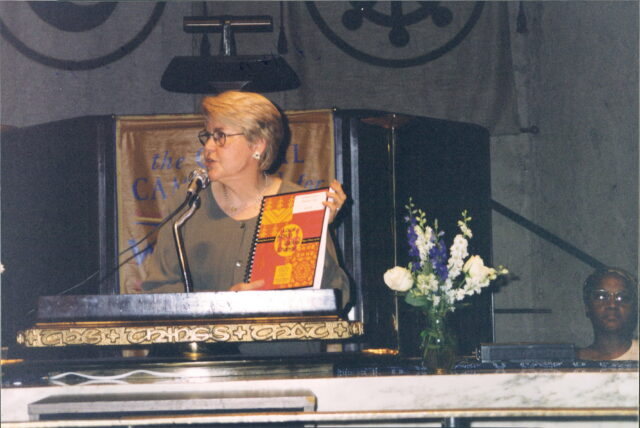

The founder and former executive director of the Center for Women’s Global Leadership at Rutgers University, she has been an activist, author, and organizer in the women’s and civil rights movements for more than 40 years. She was the also founding director of the Public Resources Center, a fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, and founder of the feminist publication, Quest. What I like most about her is that she never takes these titles as seriously as she does the ideas behind them.

There are two outstanding characteristics of Bunch’s approach to politics. First, she is a peacemaker who looks for common ground in the midst of diversity. She even agrees with the Holy See on issues of poverty. She attributes her peacemaker approach partly to her family origins.

“I grew up in Artesia, a small conservative town in New Mexico,” she explained. Her parents were Methodist would-be missionaries whose ambitions to work in China were thwarted by the Second World War. “They changed course and decided to work among America’s rural poor,” Bunch says. “I didn’t grow up thinking [that] I was in the center of the universe.”

She believes that “good” feminism affirms differences by race, sexual orientation, abilities, cultures, and religion. In her view, American feminists have to be willing to meet women from other countries on a more equal footing.

“Politically, I work as an American engaged most of my life in trying to change the US as well,” Bunch said. “During the Human Rights Conference in Vienna, we decided to present the problems of violence against women domestically in the US so that people wouldn’t think that violence is a product only of dictatorships and war.”

A second characteristic of Bunch’s politics is continual evolution: personal and political. She has trekked the rocky road from a naive campaigner for justice within the Christian student movement to socialist feminism, radical separatism, and international activism. Her early days looked very different from her today. In the 1960s, she worked mostly through the church, the YMCA, and the Methodist student’s organizations as the founding president of the University Christian movement. She soon became involved in the civil rights movement during which she confronted the blatant racism of the South and saw a world through a new prism that affected the rest of her life.

In 1966, she graduated with a degree in history and political science. Professor Ann Scott advised her to “settle down and stop [her] activism.” When Bunch asked if she couldn’t both get a degree and work in activism, Bunch responded, “OK, I’m not going to graduate school.”

Not all of her life decisions were so certain.

“I’ve had many crises of faith,” she said. “When I became a feminist and when I came out as a lesbian, I felt that the church couldn’t handle it, and I couldn’t handle it not handling it. You have to continually re-evaluate the political perspective you work from because the work keeps changing.” As she wrote in her book, Passionate Politics, she even experienced a mid-life crisis as a movement organizer, occasionally wishing that she had become a lawyer or a bookkeeper or something financially stable and accepted.

She hung on, and today, she is acclaimed as an historic leader in the women’s human rights movement. She admits to getting discouraged and angry, but she can’t see anything else she would rather be doing.

“I have learned over the years to have an openness. Life is unpredictable, and you stay engaged, open to the idea that something different happens,” she said. Her priorities include highlighting issues of discrimination in education, legal, economic, and political rights. She is particularly concerned about violence against women, which she believes is the weapon by which patriarchy regenerates its authority.

When weary from campaigning, Bunch seems to find within herself an energy that sometimes pushes the limits of common sense. Her battle against breast cancer was a sober reminder to slow down. Nevertheless, Bunch is, above all, a pilgrim in search of the root causes of injustice. On her life journey, she seems to check under each stone for a wrong decision that doesn’t measure up to her own high standards of truth and humility.

End of Section