In the off-hours of Bangkok’s busy nightlife, massage parlor workers take off their number badges and step out of their fish tank-like windows where they sit waiting for customers to choose them. Dancers unhook themselves from ropes that support their athletic prances. They gather around steaming cups of tea and catch up on the latest television soap operas. While these daily routines restore a mood of normalcy to the intense, burned-out life of these young women, everyone is aware that nothing about this life is normal. Many of them must provide sexual services, as well as entertainment and massages. Since the AIDS epidemic hit Thailand in the 1980s, sex work has become a game of hide-and-seek with death.

Non-governmental organizations, government programs, and women’s groups have made sure that AIDS awareness has reached the entertainment business. Public health clinics have been set up in the midst of the neon-lit glimmer of the infamous Patpong tourist district. The clinics show videos for health education programs nonstop for patients in the waiting rooms. Women’s groups also established outposts in the same area. Activists are determined to raise the gender bias issues. They have highlighted the plight of child prostitutes, the near slave-like conditions of massage parlors, and the sexist bias of health programs. Their mission is urgent.

I ventured into Patpong with a government health worker. An elderly Chinese couple that owned the bar greeted us with a bow and told us that they hoped the AIDS scare was just a rumor. We told them that the situation was very critical and that their cooperation would be an important contribution to remedy the problem.

As the time approached for the health education session to begin, the bar girls came downstairs from their quarters. I quickly surveyed that their faces that were freshly scrubbed and had no makeup. Some looked like they were in their teens, although they probably had false identification cards. They chattered on like Bangkok swallows, pushing close to each other as they settled into the bar booths.

When the NGO nurse arrived, the noise subsided into an obedient silence, and the bar girls sat up attentively like students starting the day with their teacher. The lights dimmed, and the slide show began with hopeful musical messages about how sexually transmitted diseases are treatable and where to go for help. A somber tone quickly replaced the gay mood. The photos were unusually explicit, showing skin sores and the cancer-eaten flesh of AIDS patients. Some bar girls looked away. Everyone was pretty frightened by the end of the slide show.

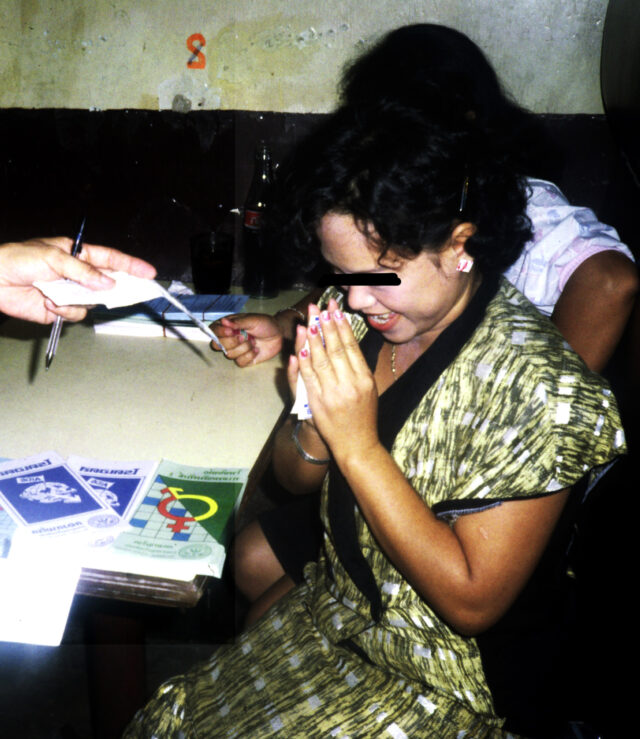

The young women were very receptive to the main message of the day to use condoms. Heads bobbed in agreement. When the lights came up, the nurse took out her packets of condoms and did a perfect finger demonstration of how they slip on. Then, she offered one packet to each girl. One by one, they knelt in front of the nurse who assumed an air of a merciful angel. The bar girls received their gifts with their eyes to the ground and hands folded in respect.

Then, one young woman dared to ask, “How can we get men to wear these condoms? Do you have any suggestions?”

“You must tell men that they might get AIDS or other diseases if they don’t,” the nurse answered with an authoritative voice. That comment ended the friendly session, and everyone said farewell.

The leader of the group of girls, known as the “men’s favorite,” sat down with me and my translator. She assured me that the bar girls took these education messages seriously and were grateful that NGOs wanted to help. The only problem was that they could not make men put on condoms. They couldn’t explain this to the nurse and had learned to be realistic about the tourism business.

“If we tell men that they will get AIDS, they won’t come back, and we will lose our jobs,” she said.

I compared this situation with those of some European countries where sex workers were mostly mature, assertive adults capable of organizing themselves into semi-unions. However, these bar girls had barely crossed the threshold from childhood to womanhood. From their perspective, the grand vision of the feminist movement about empowerment for young women seemed out of reach. In the eyes of Thai society, prostitutes are so-called “bad girls” who lived in a world of drugs and crime that was largely hidden from sight.

Nevertheless, a few women’s groups are working to shed light on an underground world of crime, kidnapping, and rape. Their actions are beginning to attract public attention. Prostitution is officially illegal, but enforcing the law is another matter. There are networks of sex slave traders who have cast their nets across Thailand’s hill tribes and poorer northern regions to entrap more girls. Some of the victims are as young as ten years old. The age slips lower as the AIDS epidemic progresses and the demand for virgins increases.

Feminists report the there are two underlying causes of prostitution: poverty and efficient sex trafficking organizations. Impoverished rural parents sell their daughters under the guise of paying a job broker as low as $200 to help girls find a job in a city. However, the broker is actually trafficking girls from rural villages to cities. Under changing hands many times, the victims may find themselves in tearooms as child prostitutes. Later, they are moved into the bars and massage parlors to service international tourists and businessmen.

Clients from Germany, France, and England have been lured by ads. One ad was posted by a Swiss travel group: “Slim, sun-burnt and sweet, [Thai prostitutes] love the white man in an erotic and devoted way. They are masters of the art of making love by nature, an art that we Europeans do not know.” Japanese, Chinese, Thai, and Arab businesses also entertain at establishments where customers can step into rooms in the back for a little “special treatment.”

The tragedy of prostitution in many countries, such as the Philippines, Korea and Indonesia, is that the victims have often been blamed for the AIDS epidemic. Sex workers are portrayed as the new Typhoid Marys who carry the HIV virus. Health campaigns often focus exclusively on the health education, control, and surveillance of prostitutes, rather than that of their male clients. If this was not enough, improved surveillance among prostitutes has meant that those who contract the virus lose their jobs without health insurance or job compensation to cushion the financial blow.

It is time to stop blaming the victims. Women activists have called for more legal action and health education directed at the organizers of sex trafficking and male clients. More concerted action is needed because the HIV/AIDS epidemic kills the most vulnerable women and girls. More women than men have AIDS worldwide, and UNAIDS reports that HIV prevalence among female sex workers ranged from 6.1 percent in Latin America to 36.9 percent in sub-Saharan Africa.

Let me end my story with a reminder of how rural poverty lies at the heart of the matter. Several months after my Patpong visit, I traveled to a poor northeast region near the Laotian border. I met a couple on their farm who were caring for a young child. They told me that she belonged to their daughter and that she did not have a father to take care of her. Then, they told me proudly of their beautiful daughter and how she left to find work in the city at a big restaurant. I asked the name of the restaurant, since I would go back to Bangkok and might take their greetings to her. They said that they didn’t know, but the job must have paid very well, since she sent money home every month.

I looked at the child and remembered the bar girls in Patpong. I told the couple that perhaps I will meet their daughter in the city, but I did not say where it might be—in a restaurant, bar, or hospital for AIDS patients.