I am a global citizen who has worked for the United Nations most of my life. My work has taken me to every continent. I talk about countries as if they were people, and I keep track of ten world clocks on my iPhone. In the past 12 months, I have attended meetings in Geneva with the World Health Organization and joined demonstrations at the Conference of the Parties meeting at the Paris Climate Change conference. Last month, I helped train women’s organizations in Cairo, Nairobi, and Beirut.

In every country I have visited, I have to answer the question, “Who are you?” You might think that the answer is simple. But if you are working in remote rural areas of Africa or Latin America and you look like me, the answer gets pretty long.

Me: I am the UNICEF consultant.

Rural woman leader: Yes, but where are you from?

Me: I live in Hoboken, New Jersey.

Rural woman leader: No, where are you really from?

Me: Oh, I was born in Pyongyang, North Korea, but I grew up in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

(Here, I do the “hand thing” to show the shape of Michigan.)

Truth is, no matter what I said about originally being from Korea, most villagers in Africa or Latin America that I met would be talking the next day about this Chinese UN official they met. What have I learned as a global citizen about who I am? I am an onion with many layers of identities. Some are true, some are even imagined by myself–and many are just wrong. The real me is somewhat hard to define because it is evolving all of the time. The real me is–from one situation to another–subject to change.

When we are born, we obviously have no control over our identity. According to Korean tradition, my grandfather gave me my name in Chinese characters that means “peace forever.” In many ways, growing up was a process of defining more and more of my own identity. Throughout high school, I was the prime achiever as a cheerleader, vice-president of my class, and art editor of my yearbook. Then came the rebellious years of my university days as an anti-Vietnam War activist. Long days and late nights were spent raising money to get my friends out of the Washtenaw County Jail. That was when I nearly failed an anthropology class. The one constant theme in this part of my life–in varying phases–was that I was a student.

Then came abrupt changes in my life [that] was my transition from student learner to teacher. This transition from university to work can be very jarring. One day, you are the student, asking the tough questions someone else is supposed to answer. The next day, you are the grown-up who is supposed to have the answers. I remember the first time some introduced me as an anthropologist. Was that really me now? It was–and there was no turning back.

My life in anthropology didn’t get off to a happy start. I couldn’t stick with a teaching job in East Lansing, Michigan because I couldn’t imagine myself settling into a professor’s life. It seemed like a very confining space, one that might close doors to the real world. I had lived in the United States most of my life, but my universe–the one I really lived in–was the whole world. Reading helped me imagine myself in French villages, the Trobriand Islands, and Thai villages.

I wanted to change that world hands-on and not just by writing books. When I really dug deep into my emotions and wondered where I would be happiest, I realized that I had to try to work at the United Nations. I was trying to match what was inside with how I would spend the rest of my work life. Where would I start this international journey? Even though I didn’t speak Korean, I packed my bags and left to teach at Ewha Womans University. Korea, after all, was where I started my life and where I might just find a new one.

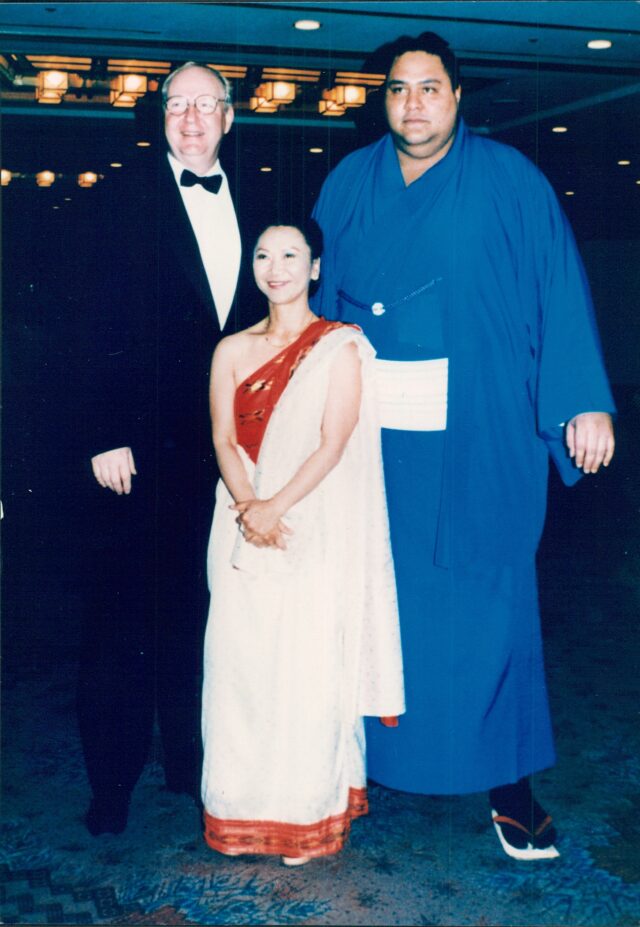

I had an interesting experience during my early days, teaching at Ewha Womans University as a Senior Fulbright Scholar. One day, my soon-to-be husband and I decided to go the U.S. Army base to have dinner. He is my biological opposite–over 6 feet tall, blond, and of Anglo-Irish descent so there was no doubt that he was a blue-blooded American.

When we got to the gate, the guard looked as us, ignored Rick, and never even asked him for proof to enter the compound. Instead, he turned to me and asked me for my venereal disease card. At that time, I guessed that this ID was required of Korean prostitutes visiting the army base to prove that they were disease-free. I was totally puzzled, but I showed him the only ID I was carrying with me that allowed me to enter the grounds. It was a Fulbright U.S. Embassy pass with my photo on it. The guard let us in.

Here’s another case of mistaken identity that was not as funny. In the 1970s, I was travelling to Jordan with a Palestinian couple in my new French car. At that time, all of the borders were heavily guarded because a Japanese woman traveling with a Palestinian couple driving in a foreign car had bombed a hotel in Amman the week before. When we got to the Jordanian border, I rolled down my car window to give the soldier my passport, and suddenly, we found ourselves surrounded by armed guards, guns pointed at our heads. They made us get out of the car, and for the rest of the day, they stripped my car nearly bare, tore out the lining of its doors, took out the back seat, and opened every bottle and package they could find in my luggage.

When I asked why we were being detained, I was told something I will never forget. The enraged soldier holding my passport, waving it in my face, said, “This is a fake passport. You are obviously Egyptian.” I was an Egyptian terrorist in the company of a Palestinian couple, on my way to bomb another hotel in Amman. We got out of this mess only because my friend was an officer in the Jordanian Air Force. By evening, someone came to our rescue.

So, I know how it feels to have a serious disconnect between my real identity and what others think of me. What is the one lesson to learn from this? Even if you can’t change how others see you, you can decide what you make of it. Will you be utterly destroyed? Is your identity totally wrapped up in what work you do? What defines your worth? I think one of the hardest battles in life to hold on tight to our own identities no matter how many times our jobs may change.

If you are wondering what to do with all these layers, try to peel your onion. I promise you can do this without crying. In fact, it may even make you happy. Being a global citizen means that sometimes you peel away all layers of nationality, age, ethnicity, and even gender until you reach the core as a human being.

When I held a UN laissez-passer (the UN equivalent of a passport), I travelled as a UN citizen, not as an American. I had to think and act on behalf of every man, woman, and child in every culture, on earth. I had to stand up for human rights, and my responsibility was to make choices fit for all of humanity.

In the development work I have done, whether digging water wells with UNICEF or advising governments about women, health and tobacco, my sense of purpose was always focused on how the UN could bring hope and dignity to those it served. Ultimately, what we strive for as global citizens is to give everyone a chance and a right to discover and fulfill their own potential, free from prejudice, poverty, and violence. What we wish for everyone is the right to define their own identity.

Everyone can peel away his or her layers of identities. At the opening of the NGO Forum during the UN Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995, I looked around the stadium at the faces of 20,000 women and men, boys and girls, and asked myself, ‘What are they doing here? Why have they come?’ For the next few weeks of that meeting, I looked for my answer–and then I found it.

One day, I walked into a tent at the NGO Forum and saw a group of women dancing the hokey pokey. These women could not understand each other’s languages. They came from different religions and cultures; they were different ethnicities and ages. But there they were, celebrating their oneness as women. They had stripped away all identities until they found a common one, and they had done this on purpose of their own free will. Somehow, through this gathering of fairly ordinary women, victims changed their identities to advocates. Those who thought they were alone felt connected to millions of women around the world. And the international women’s movement gained a momentum that cannot be stopped to this day.

So, you can see why I like being an onion. We have the power to change our identities, but we also have the power to help others be true to theirs. My parting words to you who wish to make the world a better place is this: if you want to change the world, learn more about who you are–and who you can be. (You can see this story on You-tube here)

End of Section