If you are having a bad hair day and want to try a radical look, you might want to consider how such a dramatic makeover might be received in other cultures. In some societies, your haircut reveals your cultural and possibly even your political leanings. Our coiffures are like billboards, sending instant messages “I am willing to compromise” or “Don’t you dare tell me what to do.” If you revolutionize the outside of your head, you could be projecting what is going on inside.

Girls throughout the ages have changed their hairstyles as a sign of political rebellion. You would be surprised how some patriarchal authorities have reacted. Take the famous case of the students in Sichuan province during the 1920s. At the time, girls wore long braids and did not cut their hair until marriage. Qin De-jun, a believer in equal rights for women, had other ideas. She joined a progressive group called the Intuition Society and began to dress like a man. One day, she cut her hair short, and two other female students did the same. Her style, known as the Napoleon, was straight and considered very “unfeminine.”

Qin’s mother caused a scene because she believed that cutting hair before marriage revealed corrupt morals and violated Confucian teachings. The girls had to leave school. One was sent back to her hometown. Another was forced to marry against her wishes. Qin left home and joined the Students’ Autonomous Association at another girls’ school. Social reformers had heard about her outrageous short hair and rallied to her cause. The association even organized a play about her haircutting incident.

The Napoleon and Washington hairstyles eventually turned into a movement that swept the province. Conservative parties rallied against the students and alerted the police, saying that if the girls were allowed to continue, their rebellion would affect the morality of the state. As a result, the police issued a prohibition on short haircuts for girls. Unfortunately, for parents, placing a ban on hairstyles rarely lasts. When you walk down the streets of modern Beijing, you can easily assess which side of this controversy won.

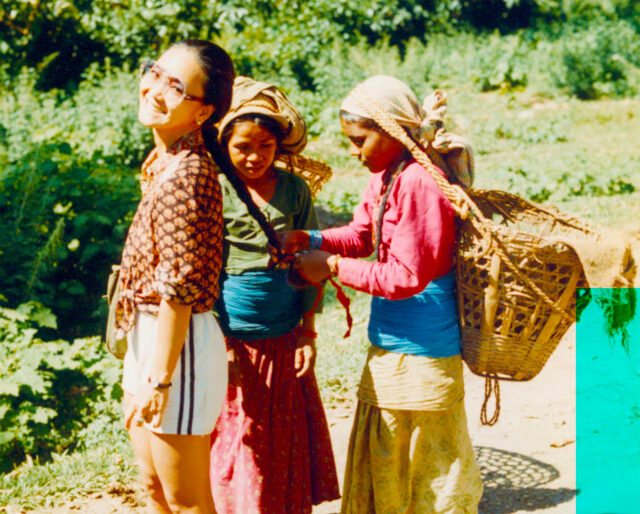

There is a boys’ side of this hairy tale as well. In most cultures, femininity is identified by long hair, so boys who let their hair grow out are believed to have crossed the gender line. In several cultures, long hair for boys is taboo. Before Princess Diana’s visit to Nepal in 1993, the Nepalese police rounded up long-haired boys in the streets and shaved them into crew-cuts in an attempt to make them more “respectable.” The move backfired, and the young men earned a lot of public sympathy. Newspapers carried editorials with titles like “Spare my hair” and “Long live long hair.” There were also serious stories about the boys’ human rights and hair rights.

If you think that making decisions about your hair are important, you’re dead right. Also, if you live in a society where you–and not the police–are the ones to decide how your hair looks, be thankful, live it up, and try something new. I hear that Jell-O makes a good green.