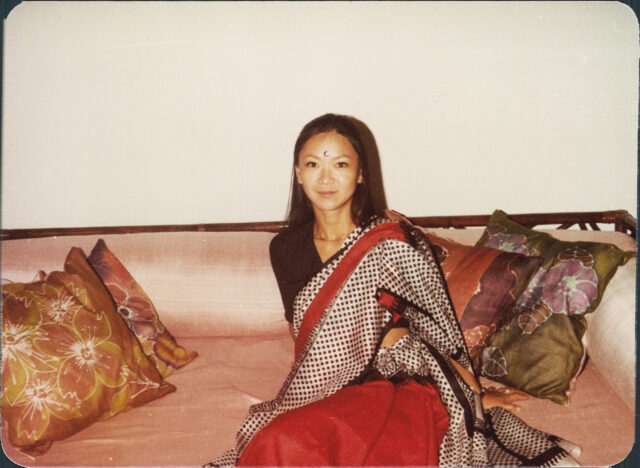

During a meeting at the Asia Institute for Science and Technology in Bangkok, Thailand, I approached a student to ask about Canada’s foreign assistance in South Asia. However, the topic of conversation quickly changed when I couldn’t take my eyes off the black plastic dot that decorated her forehead. Known as the bindi, the dot is a common accessory for young Indian women. In this case, its large size almost overwhelmed the symmetry of her eyes.

“That sure is a big bindi,” I said. She laughed and lifted her eyebrows to animate the bindi into a playful wiggle. Everyone has a distinguishing trademark, and this was hers.

“I’m known for my big bindis,” she explained.

I asked her opinion about the origin of the bindi. “For most modern Indian women, it is just a decoration like a nose ring or bangles,” she said when I asked for her opinion on the origin of the bindi. “I suspect men invented it to distract other men’s attention away from their wives’ beautiful eyes. For me, a bindi is a decoy. It’s the first thing that strangers see before our eyes meet. It gives me a chance to give them a quick look-over.”

The foreign aid debate was put aside. The origin of the bindi had to be settled. A small group gathered around to listen to my theory. I had heard that the bindi originated in religious rituals. After prayers, Hindu priests always bless male and female devotees with red powder called the tika. Some scholars say that the tika is a religious symbol representing a drop of blood of demons killed by the goddess Durga, a marker of victory of good over evil. Now that’s the kind of cosmic power everyone should be proud to carry around on their heads.

What about the bindi from a feminist perspective? According to custom in rural India, only married women have the right to wear it. Young girls are not allowed to do so, and widows must give up their bindis. The discussion was rapidly turning into a feminist critique of the bindi. We questioned why widows didn’t have the right to adorn their heads any way they wish. One observer pointed out that maybe widows were happy to be free from the mark.

“I think the bindi was originally used to mark slaves,” said a student, “and married women in India are slaves to their husbands.” That remark promoted a lot of muttering in the affirmative, and it looked for a moment as if these students were going to take to the streets in a mass revolt.

Cooler heads prevailed at the end of the day, and there were no demonstrations. Some young women noted that old taboos are changing these days. It’s unclear whether the bindi symbolizes women’s spiritual power, marital bondage, or maybe some kind of natural fashion sense. The bindi is obviously in the eye of the beholder. Whatever its origins, this simple plastic dot on a person’s forehead is clearly full of cultural meaning and deeply embedded in issues of identity. More research needs to be done.

For now, my conclusion is simple: bindi is as bindi does–and big bindis do it better.