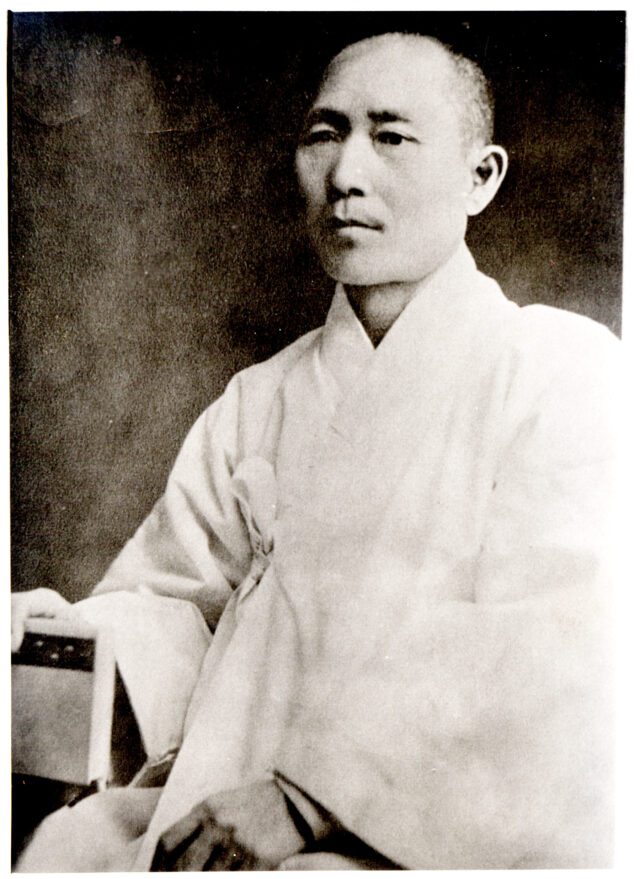

My maternal grandfather, Song Sang-Chum, was an unusually tall man of over 6 feet tall. His hair was cut short in a similar style of school boys, and he often dressed in white Korean traditional clothing. He was known as one of the most innovative modern leaders in Pyongyang at the time.

An ardent advocate of social equality, he wanted his family to dedicate themselves to Korea’s modernization in an effort to protect Korea from foreign powers. At the turn of the 20th century, Pyongyang was the industrial center of the country and under Japanese occupation. However, when compared to the West, it lacked modernized agriculture or a strong manufacturing sector.

My grandfather’s problem was that he had only one son and many daughters, so he raised his independent, assertive daughters to join his “development corps.” He told his friends that his girls could beat any boy at almost anything. He was determined to educate them abroad, so they could bring back the best of foreign ideas. He wanted each child to learn different skills in Western medicine, the arts, agriculture, and education. He also believed that Japanese military rule could be overthrown if Korea could have a strong economy.

The first child to study abroad was my mother’s sister, Song Pok-Shyn. A slight person with a fragile physique and nerves of steel, she went to a missionary high school for girls in Pyongyang and was excited about opportunities abroad. My grandfather wanted her to study modern medicine, so even before she went to medical school in Japan, he built a Western-style hospital in Pyongyang.

His plans went astray when my rebellious aunt joined the anti-Japanese underground. She worked as a secret courier, carrying messages for the provisional government in Manchuria. My aunt was eventually arrested, imprisoned, and tortured for her anti-colonial activities. She fled to the United States and was told to never return. Through sheer determination, she received a Barbour Scholarship at University of Michigan. She became the first Korean woman in the United States to earn a PhD in public health in 1929. For the rest of her life in the United States, she continued to open doors for women’s equality.

My aunt was a great help to my mother, Song Kyung-Shyn– a soft-spoken musician– who charmed everyone with her playful wit. When my mother was a little girl, she dreamed of studying piano in the United States. She had already toured China with the Pyongyang Symphony Orchestra at the age of ten (unchaperoned by my grandfather). What still amazes me is that he even accompanied her to late night rehearsals with the orchestra on the outskirts of the city. He bought her a German piano and agreed that she could go abroad to study. At age 16, she entered the American Conservatory of Music. When she finished school, she returned to Pyongyang and married Yoon Doo-Sun, my father, who was a gifted businessman and composer. They achieved their dream of establishing the first Western-style music conservatory in North Korea.

However, times were troubled, and our family’s future was threatened. The Russian army seized our house and turned it into its headquarters. It was time to leave. Eventually, the entire family made its way hundreds of miles from Pyongyang to Seoul. Within a few months, we were heading to a new home and a peaceful life in the United States.

Through my aunt’s diplomatic ties in Washington, D.C., she arranged for a U.S. military ship to give us safe passage from Busan to San Francisco. John A. Hannah, the former head of USAID and then-president of Michigan State University, invited my parents to teach music. Thus, my parents re-established their lives in Michigan. They could rebuild their lives from nothing because they had carried with them a treasure that no one could take away: their education.