In the late 1970s, South Korea’s economic miracle was in full swing. President Park Chung-Hee had a leadership style reminiscent of Japanese colonial rule. Many of my friends were arrested and tortured by the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA). Labor union leaders and protestors disappeared without a trace. The Christian-inspired urban labor movement was in turmoil, its human rights principles entirely at odds with the dictatorship. Throughout this period, student protests and proclamations for the freedom of imprisoned poets, scholars, and journalists led to clashes with the police.

The women’s studies program at Ewha Womans University and its leadership training center for women rural leaders quickly attracted the attention of Korean intelligence agents. Faculty members involved were routinely harassed. What bothered the KCIA officers the most was not the idea of women’s liberation; it was the notion that women wanted to be the ones to make decisions about who and what were involved in Korea’s future.

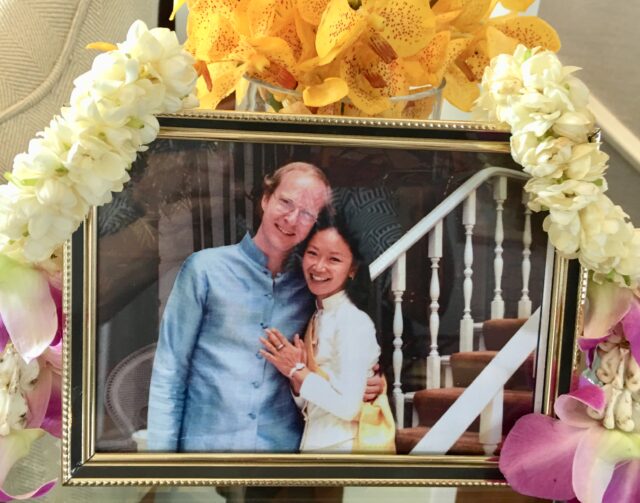

The international press also played an important role in reporting on Korea’s progress. I met Rick Smith, an editor for Newsweek magazine who wanted to learn more about the labor movement. He was a tall–very tall–and lanky young man who intimidated most Koreans in an elevator. I sometimes described him as my biological opposite with his Irish-American blond hair and fair eyes. When we walked down a busy street, both facing forward, he often complained he couldn’t hear what I was saying and vice versa. I think I grew several inches from just stretching my neck to send my voice upwards.

My research projects had put me in touch with the mother of Chun Tae-Il, a revered figure in the textile labor movement who made international headlines when he immolated himself in protest against the Park dictatorship. Rick Smith wanted to interview her and hear the other side of the story on Korea’s economic miracle. I made sure he got his story. These were the days when the government hired people to cut out censored passages of international magazines. Of course, the moment we saw the missing parts, everyone immediately sought out clandestine copies of the article. Impressed by the power of reporting the truth to the outside world, I began to take greater interest in journalists–and in him.

Rick and I were soon traveling around the country together, making both of us even more suspect to the KCIA. Intelligence agents hovered around the school residence hall, asking whether I was breaking the National Security Act by giving anti-government information to the foreign press. Agents were also obsessed with another question: were Rick and I married? That may seem to be an odd query by American standards, but in Korean culture, marriage information is considered basic data on par with one’s age and sex. I imagined that our files were being misplaced as one agent put us with the “married couples” files while another would separate our papers. There were other aspects of their inquiries that were less amusing.

When Rick Smith’s cover story for “The Koreans Are Coming” issue of Newsweek finally reached the stands, it added fuel to the controversy around the contrast between the growing Korean economy and a hardline dictatorship. Needless to say, it was the first of many stories he would write about Korea. He continued to ask me for interviews, and I was pleased to be quoted occasionally in Newsweek. Although we were born in different worlds, this meeting in Korea was to set us on a life journey together. We were eventually married by nine Buddhist monks in Thailand. In 2021, we celebrated our 43rd wedding anniversary.