When people ask me if the UN can make a difference, I think of one positive example. At the UN headquarters in New York, air pollution once afflicted many of us attending the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) meetings. The source wasn’t noxious fumes from automobiles contaminating the indoor air. Rather, there were clouds of carcinogenic particles billowing over our heads and right under our noses in the Vienna Café. Cigarette smokers of all genders and nationalities were everywhere. If the World Health Organization had done an air pollution test, it would have clearly declared this area unfit to support life. Yet, in the 1990s, smoking was permitted in this public area.

I wasn’t so upset that women and men were indulging in cigarettes. After all, the sign posted near the trash only said that smoking was discouraged, not banned. I had more selfish notions in mind. Since I had kicked the habit years ago, I was determined to not let all the smoke tempt me. As it turned out, there was no escape.

Ironically, women’s health was a priority topic on that year’s CSW agenda. In a nearby conference room, the NGO Committee for the CSW on Mental Health was having intense discussions about women and substance abuse. I was listening to a doctor discuss drugs in the workplace when I got a distinct whiff of cigarette smoke. It had to be coming from the vents that circulate the air throughout the building. There was no way to open a window; there weren’t any. Anyone who has sat in a restaurant’s no smoking section knows how that feels. Air roams freely with total disregard for any signs and into every corner of a building.

“Why doesn’t the UN do something?” complained one NGO participant. “If the UN delegates don’t set an example, how can they expect the rest of the world to stop smoking?”

Someone defended the UN, noting that in many buildings, including the World Health Organization headquarters, smoking was banned. We were puzzled about where to submit an appeal because no one knew who was responsible for the UN house rules. Whoever it was, they might consider that building workers and food servers could easily sue for prolonged exposure to air pollution if they developed respiratory diseases.

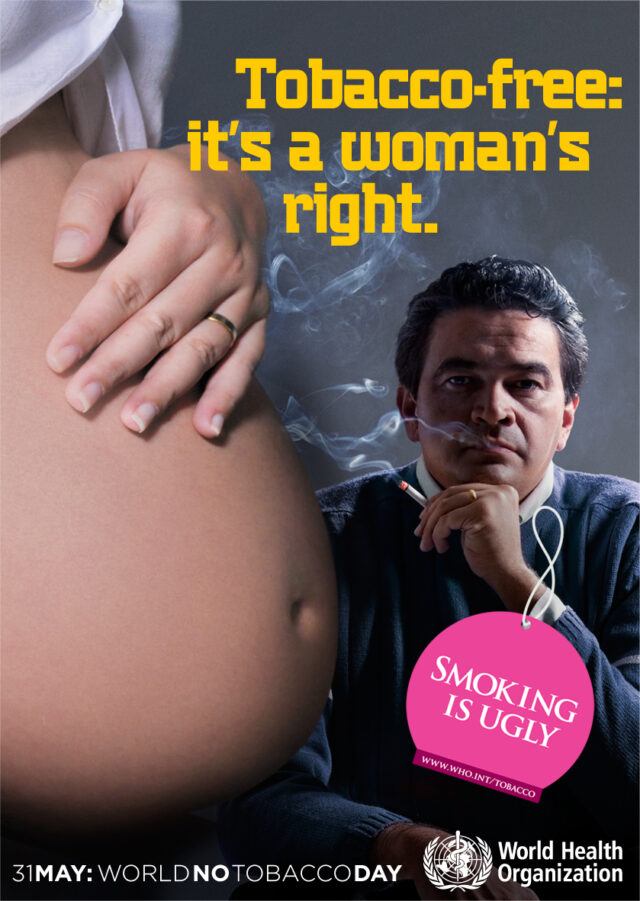

The tobacco problem aside, everything else was going smoothly at the CSW meeting. The Committee to Elimination all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) completed its elaboration on Article 12 concerning women’s health. It is implicitly understood that it is the duty of states to act swiftly and decisively to guarantee that women can exercise their human rights to health. These clarifications were then expressed to the CSW and discussed by a panel of experts. WHO representatives speaking for the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) took a bold stand in support of the women’s health movement and decried the tobacco companies’ aggressive campaigns to promote smoking. Women’s health was getting solid political support from all major groups, who were quickly becoming instant health experts.

We were still obliged to discuss our health priorities in the polluted environment of the UN Building. When I got home, I was reminded that there is another downside to smoking: the odor. My hair, papers, and clothing were all saturated with the smell of cigarettes. My daughter asked me suspiciously if I had been smoking. Having breathed the smoke-filled air at the UN for hours, I had to answer, “Yes.”

Today, this is no longer true. Smoking was finally prohibited at UN headquarters in 2008 through a resolution of the General Assembly.