One winter night in a remote Korean village, I learned how a sacred tree could bridge the divide between human beings and nature. Located deep in the woods and up a rocky pathway, a tall pine tree stood out in the full moon’s light. Its unwieldy roots had dug deep into the rocky soil, its soaring branches lifted like a skirt in the wind. It didn’t take much imagination to see the spirits floating around its trunk and into the forests.

This was no ordinary tree. During World War II, villagers took up arms to protect it from being cut down by Japanese soldiers. Villagers revered this tree because the mountain spirit lived in it. If they pleased the tree spirit, they said that the whole village would prosper, and many children would come for generations. The local officials held an annual festival influenced by Confucianism, during which villagers made offerings with candles, incense, rice cakes, and fruits. Bundled up in their warmest clothing, the men carried heavy loads of foods and offerings to conduct the ceremonies before midnight.

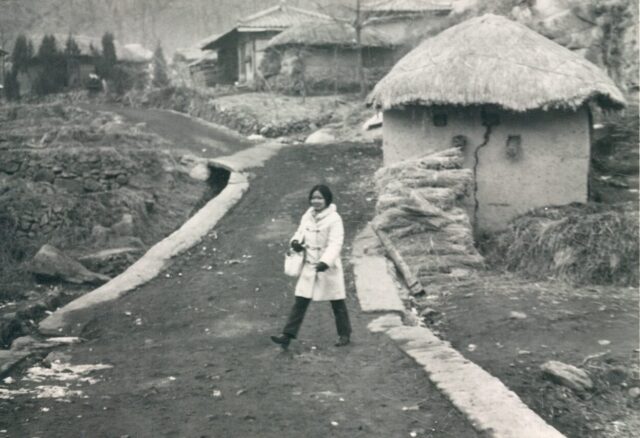

My greatest disappointment was that I was not allowed to watch the ritual. According to the village headman, no woman had ever seen it, so I decided to follow tradition. Resigned to staying behind, I joined a group making rice cakes after dinner by candlelight. We had our own party with delicious food and warm drinks. When I asked if they felt that they were being discriminated against for not being able to join the men, the women laughed.

“It is so cold outside,” one woman explained, “and the men have to carry everything up the steep mountain trail. We are much more comfortable here.” Upon hearing this, I changed my gender analysis of the situation. These women had outsmarted the men and found a way getting the rituals done by someone else.

Since then, I have learned that many rural communities and indigenous peoples hold fast to such naturalistic beliefs. Although farmers may drive tractors and wear polyester jackets, their traditional spiritual lives often survive in their subconscious. In Burma, Indonesia, Senegal and Brazil, many villagers believe that the destiny of human beings is closely connected to a web of life that includes animals, trees, rivers, and mountains. Yet these beliefs are often ridiculed, even persecuted, as superstitious and backward.

Delegates who gather at the UN climate change negotiations should take a second look at the contributions rural cultures have made to preserve the environment for centuries. Western civilization did not invent environmental ethics. Traditional cultures and indigenous peoples around the world have preserved the environment for centuries and are committed to values that can help save our planet.