There was once a little girl who was supposed to write a class assignment called “My Hopes and Dreams.” The problem was that she was unsure about grammar, so she carefully chose her words and wrote down each thought. Then, at the top of the first page, she wrote a note to the teacher, “I have written this essay with everything except the punctuation and capital letters. Since you are the expert, could you please fill these in? Thank you.”

Only a fanciful child would suggest such a collaborative approach to writing about her own hopes and dreams. It would be hard to imagine why a smart-thinking adult would surrender control of the tools that give logic and coherence to important thoughts. Yet, in the running of our economies, this seems to happen quite frequently, and usually with questionable results.

After politicians make major policy decisions, they busy themselves with governing, leaving the real business of running the economy to the so-called experts: economists, finance ministers, and development planners. Most of these professionals are more concerned with the science of social engineering than with the ethical or ideological issues of politics. There is little wonder that the hopes and dreams expressed at UN conferences often lose their meaning once the heads of state have signed the papers and gone home. The real decision-makers, otherwise the ones who ultimately write the checks, are never invited to the meetings in the first place.

If ministers of finance are to change their mission from economic development to sustainable human development, then the people who run their economies will have to become much more than economists. They will also have to be social activists who are willing to dialogue with community groups and non-governmental organizations. They will also have to become more involved in the not-so-predictable world of international diplomacy.

It would behoove to study the commitments that heads of state have made at UN conferences long ago and to take the collective ideologies expressed in them seriously. Governments might consider these four passages chosen from historic UN conferences that express important visions for humanity:

- “We, Heads of State and Government…will create a framework for action to…[promote] democracy, human dignity, social justice, and solidarity at the national, regional and international levels, ensure tolerance, non-violence, pluralism and non-discrimination in full respect of diversity within and among societies.” (Social Summit, 1995)

- “The human rights of women and of the girl-child are an inalienable, integral and indivisible part of universal human rights…The World Conference on Human Rights…reaffirms, on the basis of equality between women and men, a woman’s right to accessible and adequate health care and the widest range of family planning services…” (Vienna Declaration, Conference on Human Rights, 1993)

- “Peoples’ organizations, women’s groups, and non-governmental organizations are important sources of innovation and action at the local level and have a strong interest and proven ability to promote sustainable livelihoods. Governments, in cooperation with appropriate international and non-governmental organizations should support a community-driven approach to sustainability… “(UN Conference on Environment and Development, Agenda 21, 1992)

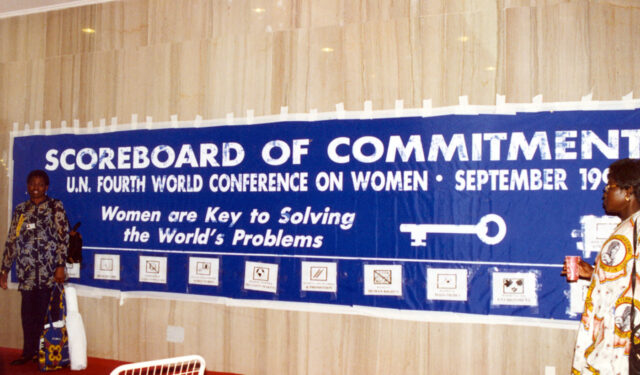

- “Existing inequalities and barriers to women in the workforce should be eliminated and women’s participation in all policy-making and implementation as well as their access to productive resources, and ownership of land and their right to inherit property should be promoted and strengthened.” (Beijing Platform for Action, UN Fourth World Conference on Women 1995)

The common denominator in these UN documents is the message that social equity, gender justice, and human rights are the real purpose of economic growth. The UN meetings that followed since these social development conferences of the 1990s have repeated and re-committed to the same principles. The question remains: why are we still talking about a stand-alone goal for gender equality and the need to mainstream gender into economic planning? Economists must be qualified to put gender equality into the long string of sound bytes that make up UN recommendations. If they do not, they may not be the best managers of women taxpayers’ dollars.