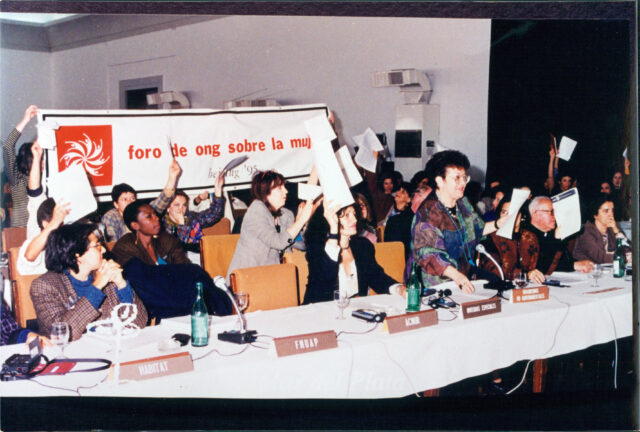

Nearly a quarter century after the international women’s movement swept through Huairou, China, at the NGO Forum in 1995, we are still pondering the magnitude and meaning of the event. Many women experienced a kind of magic that changed their lives. In the crowds, no one was a stranger. A young student from New York joined hands with a villager from El Salvador and a Chinese painter. They could not speak each other’s language, but they danced together in the Healing Tent of the NGO Forum. Who would have thought that the hokey pokey dance could be a ritual dance of empowerment?

Veterans of the first UN World Conference on Women in Mexico City (1975) could see that something was different about this UN meeting. In the eyes of some women leaders, the international women’s movement had grown-up. As one Latin American feminist put it, “Women no longer saw themselves as downtrodden victims.” Instead, they were celebrating their power and claiming their rights as citizens. The tactics had changed from confrontation as the only and main strategy to the use of mass media and successful lobbying. The result of the Conference was a new self-image: examining equality, development, and peace from women’s perspectives, not just as women’s problems.

“It was not a world conference about women, but a women’s conference about the world,” said Noeleen Heyzer, former director of UNIFEM (now UN Women) said.

In the eyes of many participants, all issues were women’s issues. Women want to redefine the structures, cultures, and values of development. The regional NGO Forum documents not only recorded women’s perspectives on health, education, and welfare, but also the development topics of international banking, structural adjustment, the environment, and international affairs.

Since the 1970s, women activists have argued that most UN and government agencies based their early development policies on a false image of women and children as passive, helpless victims of social injustice. Report after report of unequal status in education, health, and economic status reinforced this view. The state was a patriarchal father whose duty was to look after its dependents of women and children. However, the diagnosis of social ills was always incomplete because of inaccurate information and incomplete data.

The picture became clearer in the 1980s as UN and national statistics confirmed the role of women as major contributors to every country’s gross national product as workers and economic decision-makers. While development models recast their programs to fit a new image, the international women’s movement became increasingly uncomfortable with their role as victims.

A world conference shines the spotlight on a global consensus whose strength had been building before and continues after the event. The NGO Forum in 1995 was that special moment in history when visions for good were clear and the fog of ignorance was lifted. Years later at regional meetings and at the UN Commission on the Status of Women, the vision has evolved to make sure that we build unity with diversity. More than ever the “intersectionality” or multiple layers of discrimination born by women is part of the feminist framework. This concept includes migrant and refugee women, indigenous women and girls, those living with disabilities, non-binary people, and those facing racism as well as discrimination by ethnicity, religion, political, economic and social status.

Through the UN women’s conferences, and the international movements they launched, the feminist and women’s movements experienced a gradual and intentional transformation of their collective identity. Women would no longer be passive bystanders to be rescued as victims, but active participants in finding solutions to the world’s problems. Our role was not only to uplift ourselves, but to share our dreams for equality, development, and peace with the rest of the world.