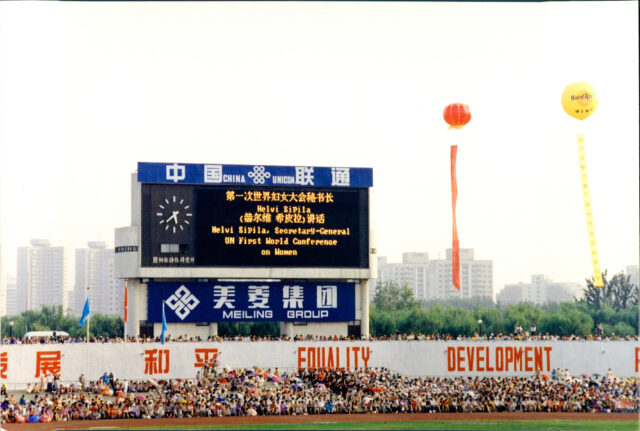

The final tally of the Beijing women’s conference’s achievements was very impressive. Here are some headlines. Governments supporting the Holy See were unable to derail the strong language that supported sexual and reproductive health and rights. Some states finally adopted the NGO amendments with reservations, a diplomatic way of saying that they agreed but disagreed. Issues about the girl-child, violence against women, and structural adjustment were given adequate attention, thus forging stronger commitments to the 12 Critical Areas of Concern, a set of priorities identified as most likely to contribute in the short-term to women’s equality.

The international women’s movement asserted its right to speak on all issues as women’s issues. Women wanted to redefine the structures, culture, and values of development, and they no longer saw themselves as victims. Instead, they established their rights as citizens. It was a matter of looking at the world through women’s eyes.

There was a search for greater commonality between women in rich and poor countries to work together. Together, they acknowledged that solutions to global poverty, environmental degradation, negative impact of the media, and new information technologies involve everyone. The rich nations of the North recognized that they too were made up of immigrant, poor, and disenfranchised groups

At the UN conference, delegates recognized that the true enemy of peace was not war between nations, but an absence of a culture of peace. Before there can be a lasting peace between nations, there must be an enduring peace in family life. There cannot be an end to global ethnic violence while domestic violence persists. There cannot be a moral separation between private and public spheres. Responsibility for domestic violence was no longer a private issue, but now a public, legal issue.

Since the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo in 1994, the concept of women’s health has been closely tied to women’s empowerment and education. Emphasis was appropriately given to health information and prevention, such for HIV/AIDS. Health services should deal with women’s complete state of well-being, mental and physical, throughout the life cycle and address the needs of girls, adolescents, and the aged.

Human rights emerged as a new moral instrument for women’s rights. It stood for more than political and civil rights and applied to the wide range of development issues, such as women’s health, education, media, and economics.

Gender as a social construct of the relationships between men and women was debated and entered into the Beijing Platform for Action (BPfA). This controversial concept affirmed that “biology is not destiny.” There are social and cultural differences that define gender inequality.

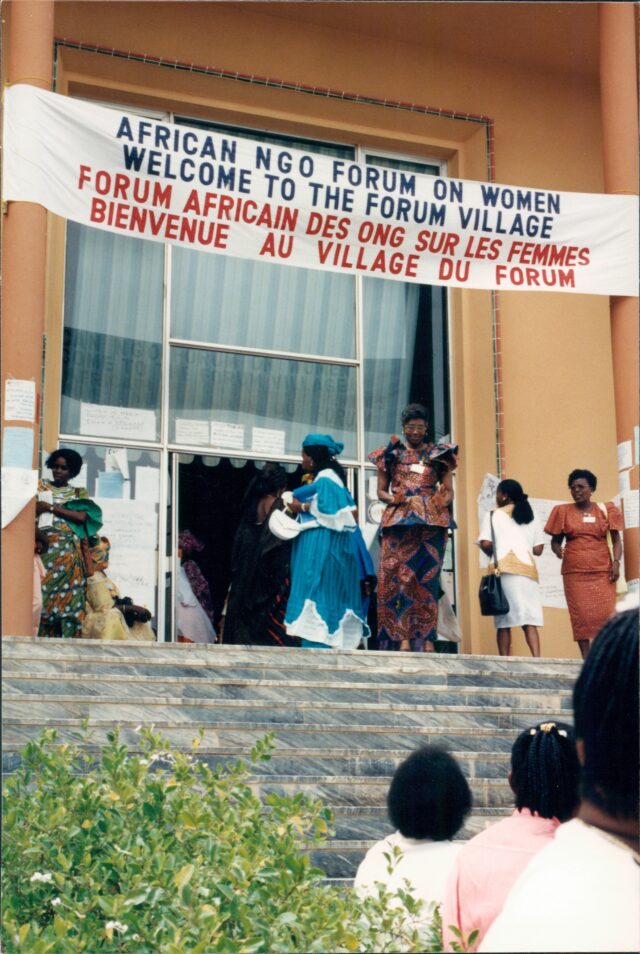

We could also count the paragraphs included. We should be proud of gains made, but the most important achievements of the BPfA are invisible. Even if governments go home and go about business as usual, the women’s movement has the potential to carry this document and make governments accountable through voting. Furthermore, this constituency is now better organized and more global than ever before. The mobilization around the BPfA and the Fourth World Conference on Women strengthened the NGO network in a spider web-like structure from grassroots to regional levels. Leadership diversified, and regional, subregional, national and subnational structures emerged with working groups and issue caucuses. These spider web-like structures continued to evolve and held on long after the conference in Beijing was over.