My true heroes shun the limelight. Some leaders are willing to assume front positions but cleverly pass on credit for their achievements to everyone else. Dr. Patricia Licuanan is that kind of leader. In a crowded room, she stands out with her well-groomed Filipino style. She usually speaks with authority, as if in a lecture hall, but she never displays a condescending air.

Most of her Filipino colleagues know her as the efficient former president of Miriam College and a professor of psychology with a reputation for extraordinary scholarly work. She earned her doctoral degree in social psychology from Pennsylvania State University and a master’s degree from Cornell University—both major achievements as she challenged the validity of Western theories during her student days. An expert on gender and economic policy, migrant women, adolescents and child-rearing practices, she also published outstanding work in conflict management and cross-cultural communications. Her research into psychology theory and extensive academic writings earned her the Psychological Association of the Philippines’ Most Outstanding Psychologist award in 1988. An active applied social scientist, she nevertheless gets her greatest satisfaction from watching students blossom and achieve. She primarily sees herself as an educator.

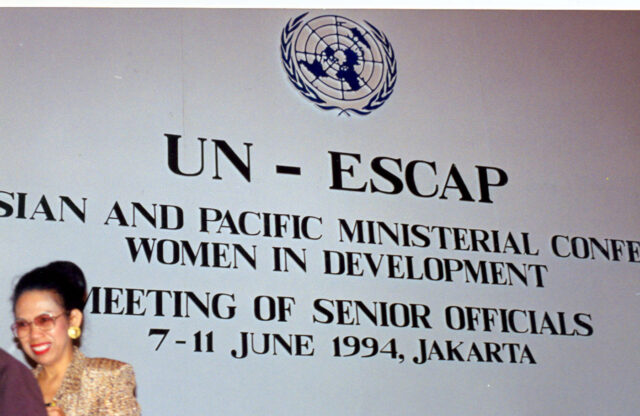

However, anyone who has seen this professor at the UN knows that she is also an accomplished politician. As head of her government delegation and former chairperson of the Commission on the Status of Women from 1993 to 1995, Licuanan acted as a facilitator and arbiter in two major UN political blocs: the Asia Group and Task Force for the Group of 77. During the 1995 Beijing Women’s Conference, she chaired the Main Committee, where the toughest issues were sent for resolution. I watched her smoothly navigate a roomful of disgruntled, sometimes hostile, delegates, many of whom viewed her as an inexperienced newcomer to the intrigues of international diplomacy. At the same time, she also had to harness discussions with rowdy NGOs and resolve tensions between feminists and fundamentalists. Something about her manner was always authoritative.

Her social psychology skills helped her untangle diplomatic knots and win support for controversial calls. Typically, she would crack a joke at the height of tensions or disarm the combatants with comments like “Hey guys, give me a break.” If you want to get the crowds’ attention in a huge UN hall, it doesn’t hurt to be a regal woman with a winning smile.

She is affectionately called “tatti” and is one of a growing number of humanist-feminist leaders who are trying to improve human welfare by looking at the world through women’s eyes. Like Wangari Maathai of Kenya and Ela Bhatt of India, she has an enduring commitment to making sure that gender equality is never forgotten and helping make miracles happen.

She is inspired in part by the Licuanan family tradition. Her great-grandfathers, both ardent nationalists, were members of the Filipino constitutional congress at the birth of the nation. Licuanan’s grandmother was a university professor and one of the country’s first women English language short story writers. Her mother wrote a daily column for The Manila Chronicle. With such pace-setting role models, it never occurred to the young Licuanan to be a traditional homemaker. After graduating from the Maryknoll High School, she went to the remote island of Mindanao to live and work with peasants.

“I was city born and bred and I never had much rural experience,” she told me. “I was an idealist and wanted to serve my country and the poor.”

When I first met her in 1977, she had taken a brief recess from her university career to work with UNICEF in Thailand. Her task was to help the organization define its first regional women’s program. She did this with her usual high energy and drive. Once she set the program into motion, she felt compelled to return to the country that she loved so well. She would never work as a UN civil servant again. Nevertheless, at every opportunity over the next two decades, she opened doors for women’s groups, NGOs, and her government to connect with regional and international projects.

After her UN days, Licuanan has continued to be a one-person support group for a myriad of organizations. As chair of the Filipino First project, she helped select 100 outstanding women leaders in the country’s history. She sat on the Board of the Magsaysay Foundation that grants the prestigious Magsaysay award for service to humanity. The Bishop-Businessmen’s Conference for Human Development, a coalition of Filipino businesses and church laity working for economic development, could count on her for valuable advice. Other research and training centers, such as the Gaston Z. Ortigas Peace Institute, sought her consultation on key policy decisions. Her schedule of international committee meetings included the ASEAN Committee on Social Development and UNESCO.

Licuanan admitted to me that she was obsessed with making sure the Beijing Women’s Conference was not a waste of time.

“I must confess that I still have my Beijing hangover,” she wrote. “But unlike with most hangovers, I am determined to nurse this one for as long as possible in myself, as well as in others, in order that the spirit of the Conference carry over into the difficult work of implementation.”

In an era of growing political cynicism and moral uncertainty, women like Patricia Licuanan stand out as role models for others. Her unflinching optimism is reflected in her belief that personal transformation is possible for everyone, even her enemies. I admire most the purity of her ambitions. She is an exceptional achiever, but if she never wins recognition, she will still persevere in a lifetime of service.