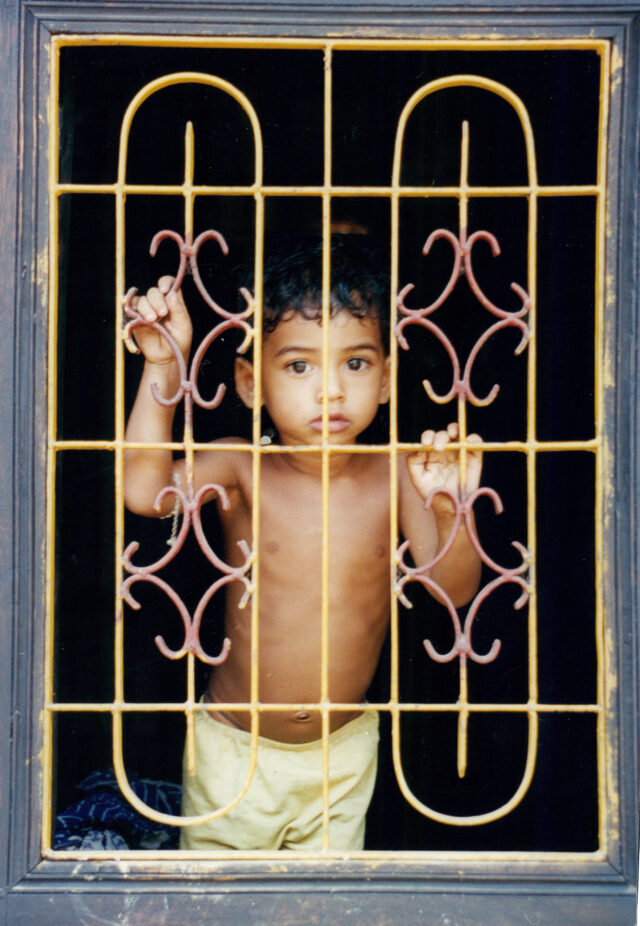

In the 1970s, many children in Lebanon were born, raised, and died in a decade of total war. Like kids in Detroit, Michigan, who can identify car models by their engine noises, Lebanese children played games to see who could tell the difference between one kind of gunshot and another. Many of them had an additional skill: how to distinguish firecrackers from machine gun fire within the first few bursts. Even these imaginative escapes had their limits. Children missed the simple pleasures of peacetime, like going out into the streets safely. Outbreaks of fighting during the day kept children from going to school. Some never went at all.

Although women’s groups and peace organizations tried to cross over enemy lines to establish peace, other leaders organized children to make sure the hostilities endured. Before his assassination, I learned about this first-hand from Bashir Gemayel, former head of the radical Christian party. Through special arrangements, I secured a tour of East Beirut with him at the wheel and armed guards in the back seat. To dodge possible car bombs, we changed cars several times before we arrived at our final destination. A fanatic militarist leader, he was proud of his plan to raise the next generation of loyal youth for what he thought was a holy war. We stopped in front a school with students in their early teens lined up in smart, scout-like uniforms.

“This is my next army,” he announced. He had realized that the wars could continue long enough for this to happen.

Distorting children’s impressionable minds to sway political allegiance has been a common strategy of dictators. Unfortunately, recruiting children into armies is also becoming more widespread. UNICEF estimates that some 300 thousand children under the age of 18 are involved in more than 30 conflicts worldwide. In many parts of the world, children as young as eight and ten years of age have been forcibly recruited, coerced, or induced to become combatants. Other grave violations include killing and maiming of children, attacks against schools, and denial of humanitarian access for children.

Lest we think that this only affects boys; up to 10 percent of children carrying arms are girls. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) General Recommendation on Women and Girls in Conflict and Post Conflict is a welcome legal instrument. Pramila Patten, CEDAW expert and then-chair of the working group for the General Recommendation, hopes that it will help to protect girls from being kidnapped by armies as well as help them to reintegrate into their communities once they return. The UN’s Office of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict was established in 2012 to give a moral voice and prominence to the rights and protection of children affected by armed conflict.

As part of preventing violence against women and girls, we must also pay more attention to what happens to boys during wartime. In countries with prolonged civil strife, such as in Sierra Leone, many children have missed the chance to go to school and develop precious ties with classmates. Instead, they might have been involved in demonstrations or have even gone to jail.

Often, children don’t have to be coerced to join armies. They volunteer because there are no options, no schools, and no jobs. Without schools to bond youth together, boys can easily be attracted to renegade groups and gangs that give them a sense of belonging. Even if they are lucky enough to attend school, they may not learn the values that would rescue them from a cycle of violence. We all know that childhood experiences help shape adult worlds. Many of us had our chances. Shouldn’t these children also have theirs?