When women are free from violence, they exercise their voice and help change the public agenda. This isn’t just rhetoric. We have good proof. When American women lawmakers turned their attention to child and maternal health, infant mortality rates dropped to 15 percent. (World Development Report- Gender Equality, World Bank, 2012).

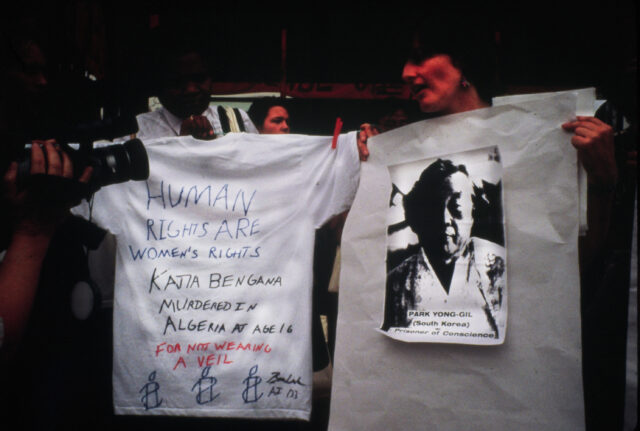

Demonstration at the NGO Forum, Beijing (1995)

It took many years for violence against women and girls to be understood. Not long ago, we talked about the silent and private agony of battered women in the home. Today, we argue that violence is a cultural problem, a societal pathology that takes other insidious forms: rape during conflicts, female genital mutilation, forced early marriage, sex trafficking, sexual harassment, and femicide. Many groups such as indigenous women, women and girls living with disabilities, the homeless, widows, and women and girls living with HIV/AIDS face multiple discriminations. The same is true for many migrant and internally displaced women, refugees, women in the military and incarcerated women. These complexities have made it hard for us to see the common denominator: unequal power relations between men and women.

One of the most powerful and least expensive ways to prevent violence against women and girls is for the world’s leaders to consistently and publicly say that it is wrong. For example, university presidents have to be more vocal about ending rape and sexual harassment on campus. Some men have already set a good example. In May 2013, President Obama stepped forward to support same-sex marriage. At that time, no laws were passed, and no enforcements were in place. However, with his public and very visible announcement, the terms of the national debate were changed. These actions helped to redefine what is acceptable male behavior and made all the difference.

We also have to be smarter about why small-scale projects aren’t working. Violence against women can’t be solved by a few school educational programs or public campaigns. We could have shelters for battered women on every city street corner, but that still wouldn’t be safe for families. Our approach has to be a comprehensive package targeted at unraveling patriarchal privilege at the core.

There is one glaring gap in our knowledge about prevention. We need to know more about why some boys become perpetrators while the majority of men do not. Why do boys who experience violence in their childhood home grow up to batter their spouses and children? Why do men who have experienced childhood traumas and conflicts survive and become advocates for ending violence against women and girls? Without a global, multi-country study that identifies risks, protective factors, and causes for men and boys, we are left in the dark about how to tackle prevention and when it must be implemented in the men’s life cycle.

I think the UN is an ideal place to tackle the issue globally because violence against women and girls is the most universal and pervasive kind of human rights violation. The founding principles of the UN include development and peace for all women and men equally as a human right. I have great respect for the many UN policies and legal instruments on hand, like the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and its Optional Protocol. These instruments carry the weight of the world’s opinion and are the beginnings of policy and legal reforms at national levels. They are our main tools of defining standards of justice and social norms. Let’s begin to leverage the power of global consensus.